For Auction, June 1st 2024

This interesting looking box is made from a golden-toned oak wood, and has a story to tell…..

It’s a tea caddy, intended to hold tea. The mounts are very early, beautifully inscribed and cast in the baroque or earliest rococo manner. Inside, it is lined with a tinned paper for this task.

According to the story that comes with it, it dates to circa 1735.

However, its story is far from that simple.

It even has a link to a legendary personage of Ceramic History fame in England, John Dwight of Fulham.

As a ‘Tea Caddy’, it is an anomaly; tea caddies do not appear like this in the 17th century. A casket for precious items or documents would be possible, but not a tea caddy, as they were not yet in use in the 17th century: tea was stored in metal or glass. The ‘tea caddy’ this piece appears to be would be early 18th century at best, but it is also a bit too small compared to others.

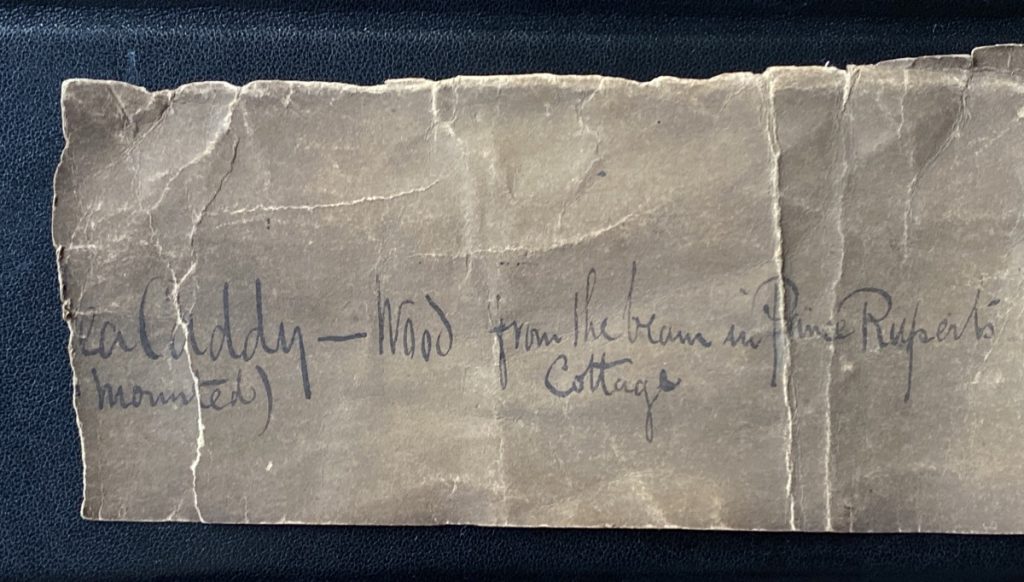

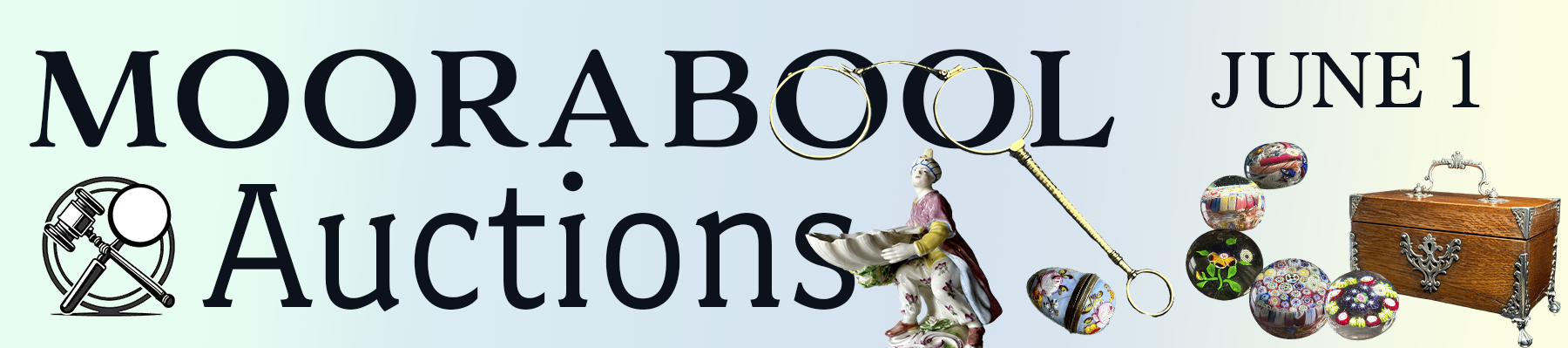

The answer to this problem lies in the various documents that came with the box. This original hand-written note explains all:

“Wood from the beam in Prince Rupert’s Cottage”

There are two cards, the first being a trad-card for ‘ALSONS & HALLLAM, Goldsmiths & Silversmiths , 69 Cornhill, EC3’ (London). On the back of this card is the jeweller’s description: ‘Antique Silver mounted Oak Casket Caddy by John Wakelyn Circa 1735’

The second is the the London adressed calling-card for ‘Mrs W. G. Hamilton’, on the back of which is written ‘With love from your Father & Mother Christmas 1938’.

These documents allow us to reconstruct the story;

In London in 1938, on the eve of WWII, Mrs W. G. Hamilton had gone shopping for a present for her son at Alston & Hallam, 69 Cornhill Street, where she purchased an amazing casket. Inside the casket was an already old piece of dark card, inscribed “Wood from the beam in Prince Rupert’s Cottage (silver mounted)”. The jeweller wrote this provenance on the back of his business card.

Mrs Hamilton wrote a brief Christmas message – with love from Father & Mother – and it was gifted to the un-named son. It may well have been sent to Australia as a Christmas present.

The next piece of evidence is a clipping from the ‘Colac Herald’ in 1970, which llustrates it in a ‘curios’ exhibition in the Colac Library, in the Western District of Victoria.

It was from here it came to Moorabool in the early 2020’s, and as the Hamilton name is engrained in the story of the Western District ‘squatocracy’, the son was probably a Hamilton of the Western District, mid-20th century.

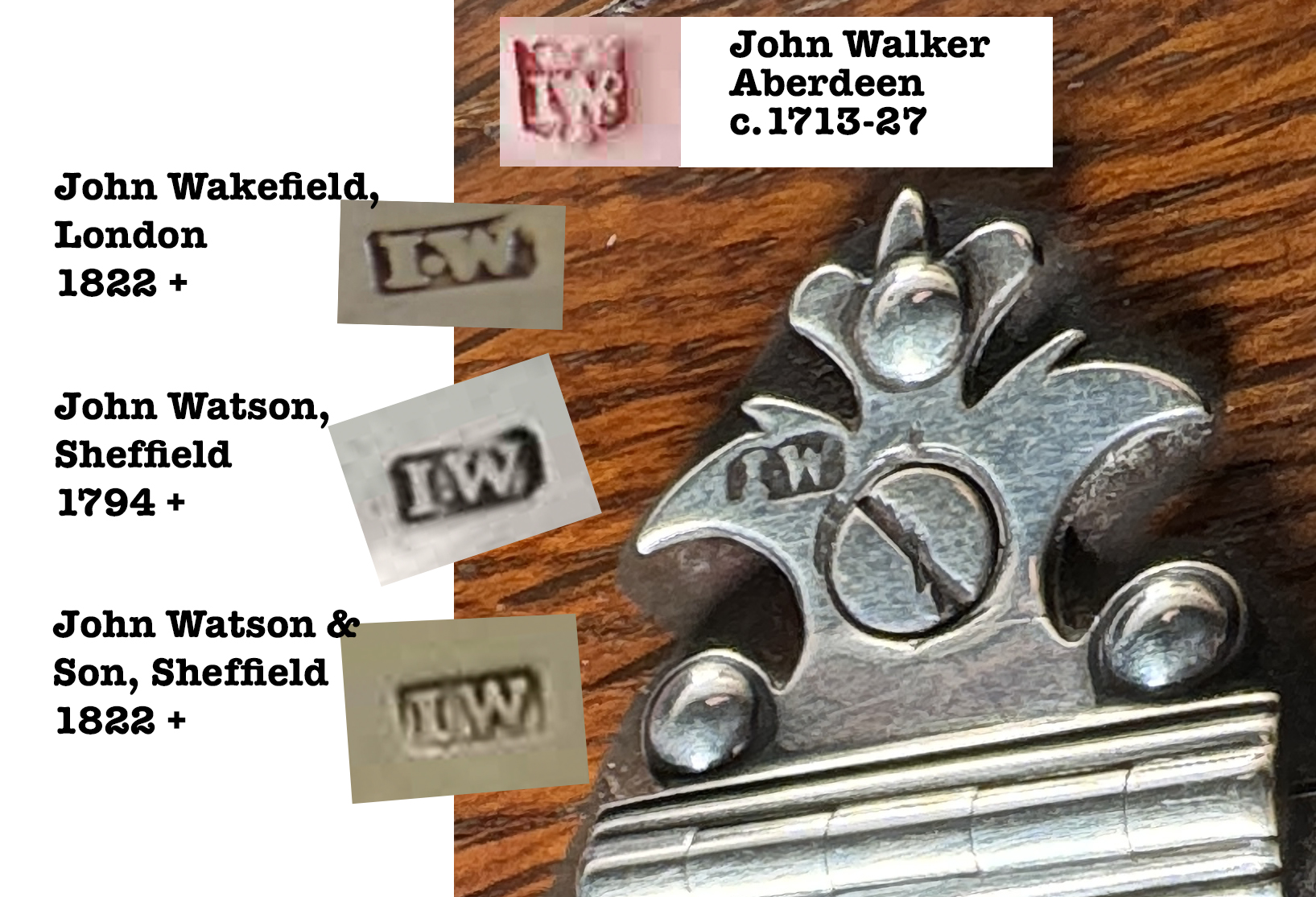

There’s a maker’s hallmark evident to the silver, ‘I W’ (ie J W), although no assay office mark. This ‘IW’ was attributed by Alstons & Hallam to ‘John Wakelyn’ and dated ‘circa 1735’ back in 1938 when it was sold. However, this is impossible, as John Wakelyn (Wakelin) seems to have been born in the 1750’s, and only active c. 1776-1805 ……

Clearly, there is a mistake. In fact, the ‘I W’. could refer to any of a number of makers: John Watson, 1790’s Sheffield, or John Wakefield, London , 1820’s to name but a few.

One intriguing possibility is a provincial origin – there is a ‘IW’ mark uncannily similar (less the edging shape) used by a rare maker, John Walker of Aberdeen, active 1713-27. This is interesting, as it would be an appropriate date for the design theme of the silver fittings.

However, it is still a rather confusing aspect, as we discover when we examine the origin of the box’s body: a beam from Prince Rupert’s Cottage.

So who was this Price Rupert of the Rhine? And what exactly was his ‘Cottage’?

The mid 17th century was a time of great turmoil for England, and the English Civil War of 1642-51 involved the struggle for England between those supporting the Monarchy (the ‘Royalists’ or ‘Cavaliers’) and those against (the ‘Parliamentarians’ or ‘Roundheads’). Prince Rupert (1619-82) was a Royalist commander. In his day, and to those generations who remembered the Civil War afterwards, he became something of a celebrity, a dashing ‘Cavalier’.

'Last of the Cavaliers....'

Prince Rupert & his dog, ‘Boy’, contemporary woodblock.

As his name suggests, he was originally from present day Germany – where his father was Frederick V of the Palatine. His mother was Elizabeth, eldest child of James I – so his English connections were strong, where he had the title Duke of Cumberland. He had been a soldier from 14 in Europe, and when called on by the Royalists in England, rose to the occasion. He became a favorite of James I, rising to the most senior post of command.

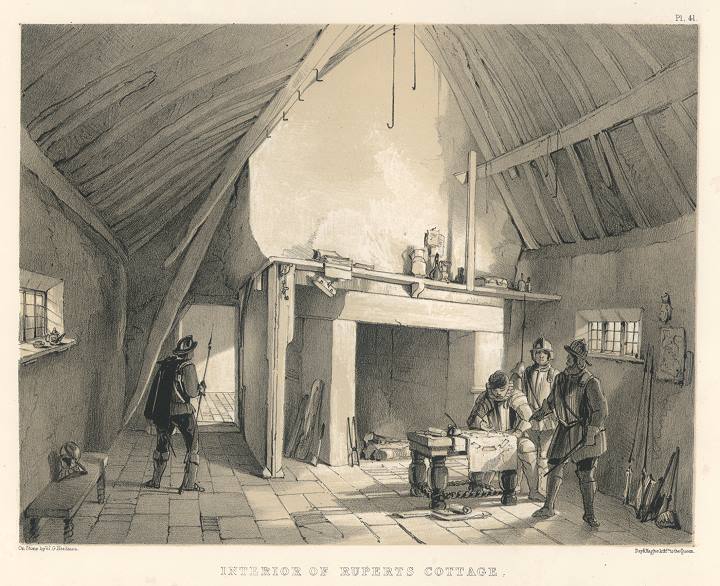

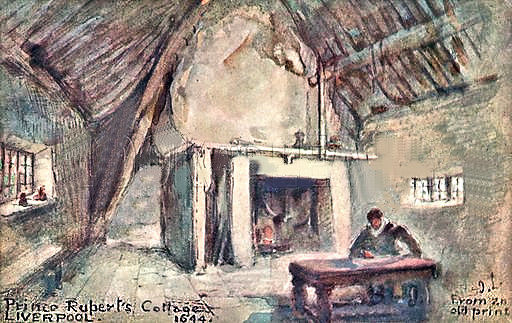

In 1643, the Roundheads overran Liverpool, and based themselves in the castle. All across the town they dug a series of trenches three meters deep….. and waited. Prince Rupert arrived in early 1644, and promptly brought in his cannon: and so the bombardment began. (18 days later, and less 1500 casualties, he finally took town & castle back for the Royalists).

In order to coordinate the siege, he commandeered a cottage with a decent view over the town, on Everton Brow. It is this house that is described as the source of the wood for this box.

An article in the Illustrated London News, 17 May 1845 illustrates the building, along with its history, noting it had just been demolished as ‘… the modern improvements in the locality …. rendered its removal a matter of necessity, not of taste’

Dating the Box

The 1845 Illustrated London News article is the key to understanding the tale of this box.

If the wood came from the cottage’s ‘beams’, it’s demolition was the source, and therefore 1845 is the earliest date of creation for the box. At this time, ‘Antiquarian’ interest in things such as the Civil War and great people like Nelson and Prince Rupert led to a thriving trade in ‘relics’ made from parts of buildings – or in the case of Nelson, his flagship the ‘Victory’. These were often useful items, such as letter openers and snuff boxes.

The box we are examining fits this scenario perfectly, and so we can attribute it to a very clever ‘curio’ creator of the early Victorian period, circa 1845.

While the before mentioned relics were made in quantity, the bespoke nature of this piece – and the apparent re-use of original early-18th century silver mounts – suggests this is a unique creation.

What a fascinating character Prince Rupert was! The British Museum states that he was “….highly intellectual with artistic and scientific interests; played an important role in the development of mezzotint as well as experimenting with gunpowder, metallurgy, gunnery, glass manufacture etc.”

Here’s a few of his mezzotints, mid-17th century, in the British Museum Collection.

Prince Rupert is also a very familiar face for anyone who has studied the history of early English ceramics: he was a celebrity in the days of the pioneering efforts of the legendary ceramicist John Dwight and his ambitious pottery works at Fulham. Seemingly to show off, he (or his sculptor, probably Edward Pierce) produced a massive almost life-size bust of the Prince in around 1680, in high-fired stoneware – an extraordinary feat that now resides in the British Museum.

Also the British Museum, there is a magnificent bracket clock that was apparently designed by him, and dozens of his engravings and lithographic prints.

These are fascinating, showing his strong interest in the arts. A box such as this one is a fine tribute to him indeed!